By: Ayesha Babar

Abstract

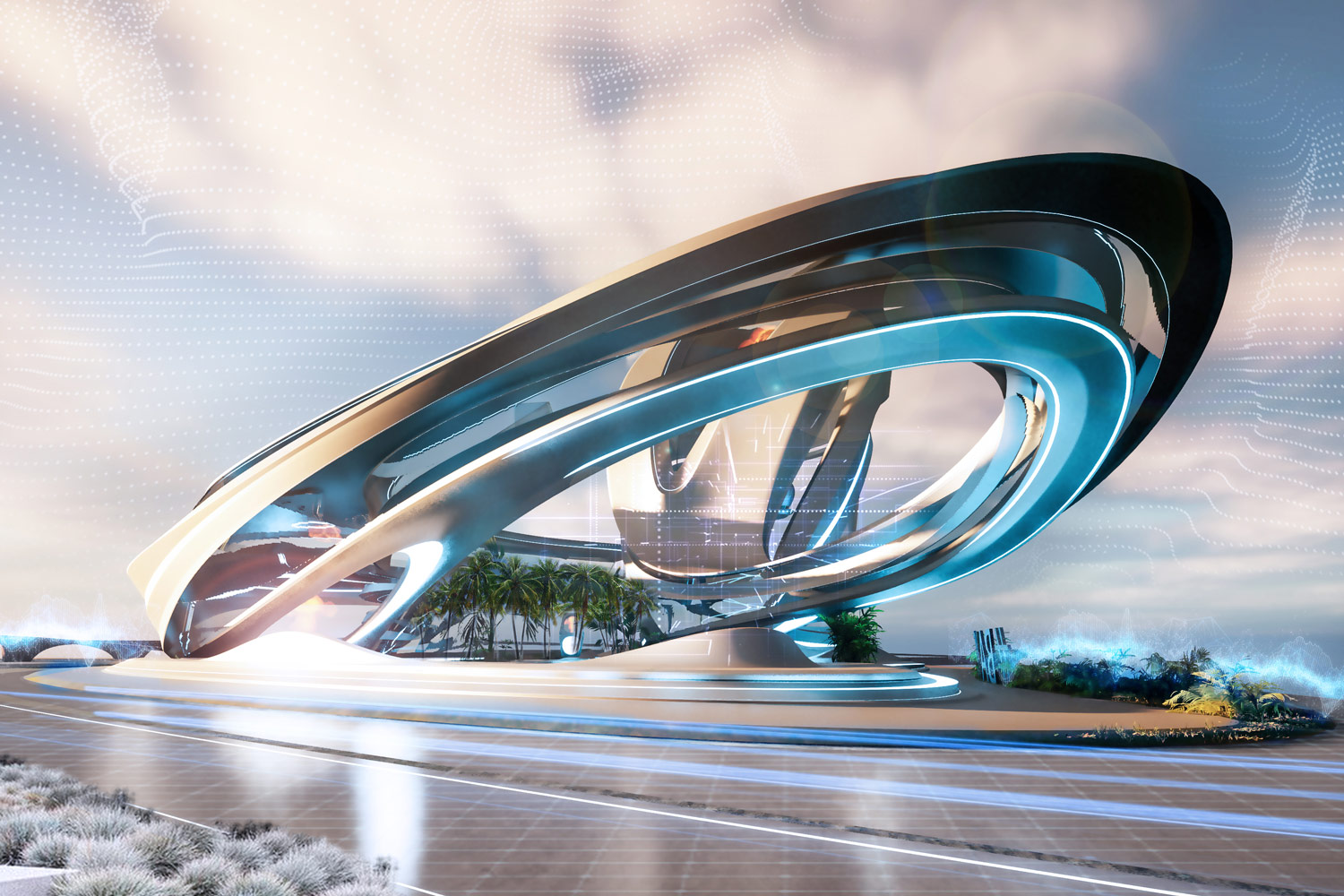

Digital tools have reshaped architectural design, empowering architects to break free from traditional limitations and pioneer innovative forms. This study explores how digital architecture transforms not only design processes but also the cognitive patterns of designers. By tracing the journey from analog beginnings to advanced computational methods, we compare pre-digital and modern approaches to uncover the dualities of digitalization, its challenges and opportunities. Insights from surveys and interviews with students, educators, and professionals highlight the nuanced role of digital tools in concept development and visualization. While, these tools boost efficiency and creativity, excessive reliance risks diluting foundational ideation. The findings advocate for a hybrid methodology that harmonizes manual and digital practices, ensuring technology amplifies, rather than replaces, human ingenuity.

Keywords: Digital architecture, design innovation, computational tools, manual techniques, architectural pedagogy

Introduction

Architecture mirrors human progress, adapting to shifts in thought, tools, and materials across eras. Historically, architects relied on manual methods constrained by physical tools, limiting creative expression. The rise of digital technologies has dismantled many barriers, revolutionizing how designs take shape.

This paper investigates how digitalization, past and present, redefines architectural practice. Earlier generations pushed material and technical boundaries to create iconic structures, demonstrating ingenuity within limits. Today, computational tools unlock possibilities for complex, once-unthinkable forms. Yet this progress sparks debate: does software dependency erode core design principles? Could over-automation weaken the critical thinking vital to conceptual work?

This research bridges historical context with modern practice by examining the interplay of traditional and digital methods. Through case studies, industry trends, and voices from education and practice, we unravel how digital tools shape contemporary design. The goal is to champion a balanced approach—one that merges the tactile intuition of manual techniques with the precision of technology to foster innovation rooted in tradition.

Literature Review

Architectural design has always evolved alongside technology, each advancement redefining creative possibilities. This section maps the trajectory of digital architecture, from its philosophical roots in post-Enlightenment thought to today’s computational breakthroughs.

Post-Enlightenment scholars like D’Arcy Thompson linked form to external forces, framing morphology as a dynamic interplay akin to natural selection. Early 20th-century architects, such as Antoni Gaudí, embraced this thinking, using physical models to test structural logic, decades before digital tools emerged. Gaudí’s Sagrada Família, with its gravity-defying forms, epitomizes analog innovation.

The late 20th century ushered in computer-aided design (CAD), a paradigm shift that pioneers like Frank Gehry exemplified. His Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, crafted using aerospace software, shattered conventional construction norms and laid the groundwork for tools like BIM. Yet this shift divided opinion: critics warned that technology might stifle creativity, while advocates praised its precision. Projects like Greg Lynn’s Embryological House or FOA’s Yokohama Port Terminal showcase digital tools enabling fluid, adaptive geometries that defy traditional spatial rules.

Education and practice further reflect this duality. Institutions like the Architectural Association’s Design Research Lab (AADRL) blend disciplines to prepare architects for a digitized world. However, concerns linger about diminishing hand-drawing skills and conceptual depth.

In sum, digital architecture is both a catalyst and a controversy. By grounding modern practices in historical context, this review argues for equilibrium, embracing technology’s potential while safeguarding the human-centric ethos of design.

Main Body

Our era is deeply entrenched in digitalization, where technological approaches are indispensable. From academia to industries like manufacturing, aviation, and animation, reliance on software, and even augmented reality, has become ubiquitous. Architecture is no exception. Traditional methods such as manual drafting and physical model-making are increasingly sidelined in favor of digital tools, which streamline design, management, and presentation. Termed “digital architecture,” this shift prioritizes efficiency and clarity, enabling designers to communicate ideas with unprecedented precision. Yet, this transformation raises critical questions: How do these evolving workflows impact the architectural design process? Early skepticism centered on fears that digital tools might stifle creativity or dilute the rigor of conceptual thinking.

The design process lies at the heart of architectural innovation. Historically, 20th-century architects relied on creative problem-solving to define their styles, often contrasting traditional and integrative approaches. Today, the process emphasizes not just creation but the derivation of structurally coherent outcomes. Emerging tools now reshape this dynamic, introducing new criteria for evaluating design efficacy. At its core, digital architecture operates on a foundational principle: how we design directly shapes what we build. This interplay between method and outcome remains central to debates in architectural education, where critics argue that over-reliance on measurable digital elements risks overshadowing intuitive, human-centric practices.

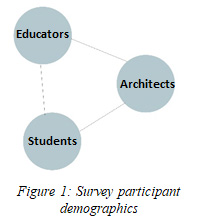

To explore these tensions, surveys and interviews were conducted with 143 participants, including students, educators, and professionals as sown in Figure 1. Data analyzed through SPSS and NVivo revealed distinct perspectives:

- Students overwhelmingly favor digital tools for 3D modeling and presentations, citing efficiency and global relevance.

- Educators advocate for a phased approach: manual techniques like freehand sketching and physical model-making are prioritized early to strengthen conceptual thinking, with digital tools introduced in advanced stages.

- Practicing Architects blend both methods. While they rely on hand sketches for initial concepts, digital tools dominate later stages for precision and time-saving renders.

Interviews underscored a generational divide. Senior professionals acknowledge digital tools’ value but caution against abandoning manual foundations. One architect noted, “You can’t start with software, sketching transfers the mind’s vision to paper first.” Conversely, students view digital fluency as essential to be competitive in a globalized field.

Survey results further quantified these trends: over 70% of respondents deemed modern tools more effective than manual methods, though 25% advocated for hybrid workflows tailored to project needs. Concerns persist, however, that automation may narrow exploratory phases of design, limiting serendipitous discoveries in form generation.

Data Visualization and Analysis

The study’s mixed-methods approach included hierarchical data visualizations. For instance:

- Tree Maps: As shown in Figure 2, the nested rectangles represent coding references, with “digital tools” emerging as the most prominent node, highlighting its prevalence in discussions.

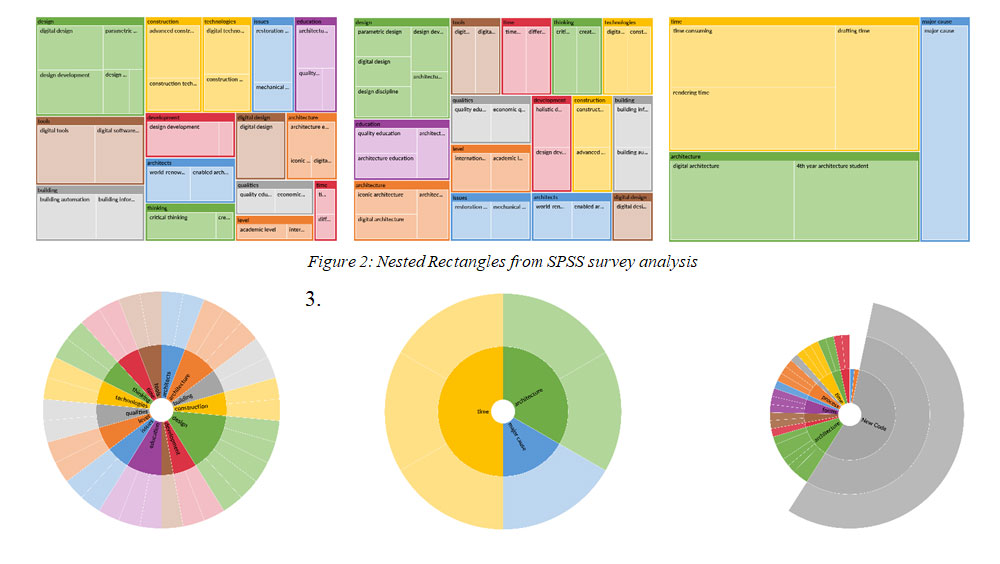

Sunburst Charts: Radial hierarchies highlighted “digital architecture” as the primary theme, while smaller segments like “time efficiency” underscored secondary priorities shown in Figure 3.

Graduate students, particularly those in master’s programs, are strongly aligned with digital workflows, viewing them as gateways to future trends. Interviews, coded into themes like “tool dependency” and “educational pedagogy,” were transcribed and analyzed in NVivo to map nuanced attitudes shown in Figure 4. Open-ended responses revealed anxieties about diminishing craftsmanship, balanced by enthusiasm for technology’s democratizing potential.

Limitations

While this study sheds light on digital tools’ transformative role in architecture, its scope and methodology present constraints. Geographically, the research focuses exclusively on Pakistan, a deliberate choice to capture regional educational and industrial dynamics, but one that limits broader applicability. Design practices in Pakistan are shaped by localized cultural, economic, and pedagogical contexts that differ markedly from global norms. For instance, architectural education in Pakistan often prioritizes manual drafting and traditional design principles in early curricula, reflecting a pedagogical emphasis on foundational craftsmanship. This contrasts with institutions in Europe or North America, where digital literacy is frequently integrated earlier into training. Such differences may skew perceptions of digital tools’ role in design thinking, as Pakistani students and professionals navigate a unique blend of analog and digital expectations.

Similarly, industry standards in Pakistan are influenced by resource availability, client demands, and regulatory frameworks distinct from those in technologically advanced markets. For example, the slower adoption of Building Information Modeling (BIM) in Pakistan’s construction sector, compared to its widespread use in countries like the U.S. or Singapore, may limit the relevance of findings to regions where BIM is entrenched. Additionally, economic constraints in Pakistan often prioritize cost-effective solutions over experimental digital workflows, potentially underrepresenting scenarios where cutting-edge tools are more accessible.

Methodologically, the participant pool, though diverse across students, educators, and professionals, remains modest in size. A larger, cross-cultural sample could strengthen findings. Additionally, self-reported data risks bias, as respondents might tailor answers to align with perceived norms (e.g., overstating digital tool adoption to appear progressive). Finally, while NVivo and SPSS enabled robust mixed-methods analysis, deeper statistical interrogation of correlations (e.g., between tool usage and design outcomes) could reveal subtler insights. Future research might expand geographically, incorporate observational studies to offset self-reporting biases, and employ longitudinal frameworks to track evolving tool impacts.

Conclusion

Digital tools have irrevocably altered architectural practice, offering architects unprecedented precision and creative freedom. Yet this study underscores a paradox: while technology accelerates ideation and execution, uncritical reliance risks diluting the discipline’s core, conceptual rigor. The findings advocate for hybridity. Students and professionals alike benefit from manual techniques (sketching, physical modeling) to nurture spatial intuition early in the design process, later integrating digital tools for refinement and presentation. This balance safeguards the human-centric ethos of architecture while harnessing efficiency.

For the field to thrive, educators and firms must collaboratively reimagine training and workflows. Curricula should emphasize foundational skills alongside digital literacy, ensuring tools augment, not replace, critical thinking. Globally, researchers must explore how diverse cultural contexts shape digital adoption, and how emerging technologies like AI might further redefine creativity. Ultimately, the future of architecture lies not in choosing between analog and digital, but in weaving them into a cohesive, adaptive practice, one that honors tradition while boldly innovating.

References

Andadari, T. S. (2021). Study of digital architecture technology: Theory and development. Journal of Architectural Research and Education, 3(1), 14–21. https://doi.org/10.17509/jare.v3i1.30500

Claypool, M. (2019). The digital in architecture: Then, now and in the future. SPACE10. https://space10.com/project/digital-in-architecture/

Grisaleña, J. A. (2017). A brief history of digital architecture. University of Alcala Press.

Papamanolis, A., & Liapi, K. A. (2014). Thoughts on digital architectural education: In search of a digital culture of architectural design. Technoetic Arts, 7(2), 95–104. https://doi.org/10.1386/tear.7.2.95/1

Sabry Abowardah, E., Sabry Abdellatif, A., & Osama Khalil, M. (2016). Design process & strategic thinking in architecture. Studocu. https://www.studocu.com/row/document/university-of-bahrain/marketing/design-process-strategic-thinking-in-architecture/12327690